Frequently Asked Questions

Frequently-asked questions about the ICZN and the Code.

What is the remit of the ICZN?

What is the difference between nomenclature and taxonomy?

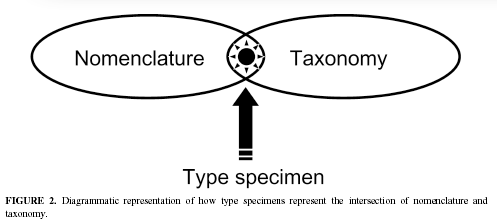

Nomenclature is the system of scientific names for taxa (such as species, genera, or families) and the rules and conventions for the formation, treatment, and use of those names. It follows an internationally agreed, quasi-legal procedure. Taxonomy is the identification and interpretation of natural groups of organisms (i.e., taxa) based on characters (such as morphology, genetics, behaviour, ecology). The discovery and delimitation of taxa is a science. Nomenclature and taxonomy are closely allied, but separate aspects ordering information about biodiversity. They overlap in the definition of type specimens, which tie the name to a single physical standard.

Further explanation excerpted from Pyle & Michel (2008) ZooBank: Developing a nomenclatural tool for unifying 250 years of biological information.

Zootaxa 1950: 1-163 (5 Dec. 2008).

Taxonomy, Nomenclature and Typification

Taxonomy and nomenclature are closely allied, but separate and complementary endeavours in developing the language of biodiversity. Discovering and delimiting species is the challenging job of alpha taxonomy; determining relationships and establishing higher taxa is referred to as beta taxonomy. Delimiting both alpha and beta taxa requires using a range of character data to test hypotheses about the inclusiveness of taxon definitions. This can naturally lead to strongly opposing alternative points of view, depending on character selection, method of analysis, and philosophical stance of the taxonomist. Definitions of taxa, from species to genera to higher taxa, can thus change significantly as the iterative process of improving the tests of taxonomic boundaries weighs alternative hypotheses and moves to new conclusions. Although it may be a source of frustration to end-users who simply want defined taxonomic entities, this process of change is a sign of the health of the science of taxonomy. Ultimately, if data accumulation were to saturate and if philosophical perspectives on species definitions were to converge, it is possible that taxonomy would stabilize and reach consensus definitions for taxa (changing only to accommodate ongoing organismal evolution). This situation is not on the foreseeable horizon.

By contrast, the establishment of scientific names of animals is not a scientific process of testing alternatives; rather, it involves a bibliographic and quasi-legal process of presentation of a name with appropriate supporting documentation in a publication. Although a scientific name is generally established within the context of a published work on taxonomy, its link to actual organisms is through the primary type specimen (or specimens). This process of typification allows the name to be tied to a physical standard (and hence provides an objective basis for identifications), but leaves room for taxonomy to change; different names can be applied to taxa as is appropriate for their new boundaries. Figure 1 presents a tree-based example, in which alternative interpretations by different taxonomists result in different generic groupings, each of which could take a different name depending on the type species of the generic group. The same process could be visualized simply based on variation, with a more inclusive (‘lumping’) perspective requiring one type specimen for a species, thus receiving one name; whereas a more divisive (‘splitting’) perspective requires names derived from several type specimens for the perceived groups. Choosing between available names for types in a group is generally governed by the Principle of Priority, such that name first established should be used for that group (Figure 1). However, even if names are not in current use for a group, if they were originally validly published they are not permanently retired, as they may well be needed in the future. Taxonomic work may split an existing group, because less inclusive taxa are more consistent with data in hand. Having older names ready to apply provides an immediate tool for recovering past information on that taxon.

We want to underscore that the work of nomenclature aims for stability in names, but is completely independent of the process of flexibility in taxonomic interpretation. This philosophy is fundamental to the ICZN's role, as articulated in the Introduction to the 4th Edition of the ICZN Code which states:

There are certain underlying principles upon which the Code is based. These are as follows:

1. The Code refrains from infringing upon taxonomic judgment, which must not be made subject to regulation or restraint.

2. Nomenclature does not determine the inclusiveness or exclusiveness of any taxon, nor the rank to be accorded to any assemblage of animals, but rather provides the name that is to be used for a taxon whatever taxonomic limits and rank are given to it.

3. The device of name-bearing types allows names to be applied to taxa without infringing upon taxonomic judgment. [etc] (ICZN, 1999: xix)

A cartoon graphic for the relationship of the trinity of nomenclature, taxonomy and type specimens is shown in Figure 2.

Last updated: 2013-05-02 18:49

What organisms does the ICZN cover?

The ICZN only applies to animal names, and not to names of plants, fungi, bacteria or viruses, which are covered by separate codes of nomenclature.

- International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants

- International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria

- International Code of Virus Classification and Nomenclature

Animals include metazoans and protists that have been historically considered in the Kingdom Animalia (i.e., protists that do not primarily use photosynthesis as an energy source, if so they are generally considered to be plants and will fall under the botanical Code, ICN). Although higher-level classifications have changed with modern research, which Code (Zoological, Botanical or Bacterial) covers a particular taxon generally remains constant, as it is agreed that the ultimate goal of nomenclatural rules is to maintain stability in names and not to reflect perspectives on phylogenetic relationships. Thus, for example, fungi remain covered by the Botanical Code, and there is little interest in changing this, despite modern consensus that they have a sister relationship with animals and not plants. Protists that have characteristics of both animals and plants are considered ‘ambiregnal’ and are treated following the rules of both the ICZN and ICN.

Fossil animal taxa and animal trace fossils, or ichnotaxa, are covered by the ICZN. Domesticated animals (defined as distinguished from wild progenitors by characters resulting from selective actions of humans) are also covered by the ICZN. Scientific names for collective groups of animals are also covered (though without anchoring on a type specimen), such as the name Cercaria O.F. Muller, 1773 for trematode larvae that cannot be placed with confidence in known genera.

The ICZN does not cover names for hypothetical concepts (e.g. the Hypothetical Ancestral Mollusc or the Loch Ness Monster), teratological specimens (monstrosities), or hybrid specimens (although taxa of hybrid origin are covered).

Last updated: 2019-02-22 13:19

Does the ICZN govern names of entities below the species level such as subspecies or populations?

Names of subspecies are governed by the Code and are available names (if they meet the criteria for proper publication). A scientific name added as a trinomen on the end of a bionomen is taken to indicate a subspecies.

However, it stops there. The ICZN does not govern names for groups below the level of subspecies (infrasubspecific groups), as is likely to be the case for populations. This also means that the Code does not regulate names of groups of specimens that differ because of intrapopulational variation such as differents sexes, different castes, age groups, seasonal forms, different generations or variants that are part of a non-interrupted polymorphism.

How can you tell if a name is intended to indicate a subspecies or a level below a subspecies? If the author adds a name on to a trinomen, then this indicates infrasubspecific rank. If the author added a trinomen (which would normally indicate a subspecies) but also used the term ‘abberation’, ‘ab.’, ‘morph’, ‘variety’, ‘var.’, ‘v.’, ‘form’, or ‘f.’ (with some specifics on dates for each of these terms, see Art. 45.6), this also indicates the entity is an infrasubspecific group, thus the name is not available according to the Code.

Last updated: 2010-03-30 11:47

Are homonyms across Codes permitted, for example between plants and animals?

Each of the major nomenclatural Codes (ICBN, ICNB, ICTV) is exclusive; they govern homonymy independently. Thus homonyms (the same name for different taxa) are allowed between Codes. For example, the genus Ficus is available and valid for both a gastropod genus and the plants commonly called figs. It is assumed that points of confusion in referring to organisms in different Kingdoms will be rare, thus homonymy is not controlled in these cases.

- International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants

- International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria

- International Code of Virus Classification and Nomenclature

Last updated: 2010-03-30 11:48

Does the ICZN govern common (vernacular) names?

No, only scientific names are covered by the ICZN. Common names may be standardised within particular regions or for particular taxonomic groups, but there is no international standardization. There are a few projects that are aiming to bring together scientific and common names such as the Pan-European Species Infrastructure (http://www.eu-nomen.eu/pesi/) or FishBase (www.fishbase.org/), but these are databasing projects and do not include a regulatory process.

Last updated: 2010-03-30 11:49

Does the ICZN ensure that the community uses the correct, properly published, available names for taxa?

The ICZN does not police the use of zoological nomenclature. The Commission rules on Cases that are brought before it by interested parties (usually taxonomists), thus acts as an arbitrator and judge, but does not seek out nomenclatural problems.

Last updated: 2010-03-30 11:50

Who publishes the Code?

The Code is written by an editorial committee of Commissioners. Drafts of each section are made available for public comment before the final text is drafted. There is an Editorial Committee currently developing a new, 5th Edition of the Code. Input is sought via a wiki at:http://iczn.ansp.org/, or issues can be discussed on the ICZN listserver.

The Code is published by the International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature,http://www.iczn.org/The_Trust.htm, which thus holds the copyright. The Trust (ITZN) is a not-for-profit scientific charity that is supported by institutional subscriptions, donations, and grants. Copies of the Code are available for purchase from the ICZN Secretariat.

Last updated: 2010-03-30 11:51

Is the Code available in foreign languages? Are the translations authoritative?

The English and French versions of the Code hold equal authority. There are a few points where linguistic differences cause a problem in determining the authoritative meaning of these two versions. The next edition of the Code will have English as its sole authoritative text.

The Code has been translated into Spanish, French, German, Russian, Japanese, Chinese – traditional and simplified, Czech, Ukranian, Catalan and Greek (introduction only). These are variously available as PDF through the ICZN or sponsoring society websites, or as hardcopy for purchase. Details are available on the ICZN website.

Last updated: 2010-04-13 19:39

Can the Commission over-rule the Code? What is Plenary Power?

The work of the Commission is to consider how to interpret the Code and when it should be over-ruled to maintain nomenclatural stability and universality. Plenary power (Arts. 78.1 & 81) allows the Commission to suspend application of any particular provision of the Code; to do so requires a Case be considered under the rules of publication, voting and the result (the ruling) needs to be published in an official Opinion. The Code does not operate on precedent – each Case is considered on individual merit – thus past rulings do not affect how the Code is interpreted in the future.

Last updated: 2010-03-30 11:52

What do I need the ICZN for? What can I do myself?

The Articles of the Code are designed to enable zoologists to arrive at correct names of taxa. The Code provides guidance on establishing new names, rules to determine whether any existing name is available and with what priority, whether it requires amendment for correct use, and how to determine the name-bearing type. If the path to resolution is laid out clearly by the Code, you may publish your conclusions without involving the Commission. If resolution of a nomenclatural problem is best served by overruling the Code, you should make an application to the Commission.

You can ask the Secretariat for guidance on whether you should apply to the Commission. You may send an informal enquiry (iczn@nus.edu.sg) or draft a potential application, which will be sent for review to a subset of Commissioners before initiating the process of publication and vote, if that is deemed necessary.

Last updated: 2019-02-22 13:26

What is The Code?

What is the Code?

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (Code) is a set of rules and recommendations on the naming of animals. It regulates nomenclature only - i.e. the way animal names are created and published (made available) - not taxonomy (classification). The aim of the Code is to provide the maximum universality and continuity in the scientific names of animals, i.e. to ensure that any given animal taxon is known under one universally recognised scientific name. The need for a code of zoological nomenclature was recognised in 1842, addressed by a committee that included luminaries such as Richard Owen and Charles Darwin and executed in a set of rules drafted by Hugh Strickland. This was adopted by major scientific bodies in Europe and the U.S. The Stricklandian Code was further developed, with increased universality across animal taxa and including the needs of work on fossil taxa, and resulted in the Règles internationales de la Nomenclature zoologique in 1905. The first edition of the Code with its modern structure was published in 1961; it is currently in its fourth edition.

Last updated: 2019-02-22 13:35

What is covered by the Code?

The Code governs names of animals from superfamily to subspecies levels.

Last updated: 2015-01-29 14:05

Is the Code a Legal Document?

No. Adherence to the Code is not compulsory, and zoologists apply its rules voluntarily, to avoid the chaos that would result if the naming of animals was not regulated.

Last updated: 2010-03-30 12:15

How is the Code revised?

The Commission on Zoological Nomenclature is responsible to revise the Code (currently in its 4th edition), in consultation with the zoological community. The Commission can also publish amendments to modify provisions of any current edition of the Code (see for instance http://www.iczn.org/Declaration44.htm, http://www.iczn.org/electronic_publication.html).

Last updated: 2010-03-30 12:16

How can I give input into the next edition of the Code?

Input from the zoological community is sought: comments can be sent directly to the ICZN Secretariat (iczn@nus.edu.sg) or to Dr Francisco Welter-Schutes, chairman of the Editorial Committee (fwelter@gwdg.de).

Last updated: 2024-02-28 15:00

When will the 5th edition of the Code be published?

An Editorial Committee under the ICZN is currently working on a proposal for a very detailed revision, and when ready, it will be made available for a one-year review period. The proposal will be widely publicized and hopefully stimulate discussions in the taxonomic community and among relevant stakeholders, and all comments and suggestions that are directed to the Commission will be considered before the final version is crafted.

Last updated: 2024-02-28 15:00

How should zoological names be written?

What is the standard format?

Zoological names are written in a standard way so they can be easily recognised, avoiding confusion, and supporting the key aims of the ICZN to make the names of animals universal and stable.

For example, the scientific name for the honey bee species is Apis mellifera Linnaeus, 1758. The binominal part of the name is in italics or some other distinguishing font or underline to indicate that this is the universal scientific name. The person who first described the species Apis mellifera in a published work was Linnaeus in 1758 and that he described it as a member of the genus Apis.

Honey bee, Apis mellifera Linnaeus, 1758.

What is binominal nomenclature?

What is binominal nomenclature?

Following the principle of binominal names (i.e. composed of two names) a species name is a combination of genus name and species name. The genus name comes first, and must start with a capital letter, the species name second, with a lower case letter (Art. 28; Appendix B6). This shows the hierarchy between genus and species; a genus may include a number of different species.

Last updated: 2010-03-30 12:47

Should all names be written in italics?

The genus and species name are conventionally written in italics (or more rarely another contrasting typeface) to distinguish the name from surrounding text. This is desirable and recommended, although not mandatory (Appendix B6).

Last updated: 2010-03-30 12:47

What kind of alphabets and symbols can be used?

Only the 26 letter Latin alphabet a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, I, k, l, m, n, o, p, q, r, s, t, u, v, w, x, y, z can be used for species names (Art. 11.2). Generally the spelling used in the original description is followed (Art. 32). However accents or other marks, e.g. “é”, “ø” are corrected, gaps apostrophes and hyphens (except rare instances) are removed and numbers spelled out in letters (Art. 32.5.2).

Last updated: 2010-03-30 12:48

Can names be shortened to save space?

In each written work it is advisable that a species name is written in full at first (rec. 51A; Appendix B10). The name of the author is optional although customary and often advisable (Article 51). This helps to avoid confusion between similar names and also shows which taxon concept is meant. Later mentions in the same paper can be abbreviated where this will not cause confusion. For example the genus name can be abbreviated to one (or rarely more letters – Appendix B11) and the author and date omitted. A few very well known author names such as Linnaeus (L.) and Fabricius (F.) are conventionally abbreviated.

For example: Apis mellifera Linnaeus, 1758 can be written as A. mellifera L., 1758 or just A. mellifera.

Where there are more than two authors, the term et al. can be used after the first author to save writing all the names out in full again (Appendix B12).

Last updated: 2010-04-29 11:57

Why are there sometimes brackets around the author name?

Sometimes a species is transferred to a genus other than the one in which it was originally described. In this case the author name and date is put in brackets to show that it has been reclassified.

For example the lion was originally described by Linnaeus as Felis leo but over time knowledge of the cat family developed and the genus Felis was split up; the lion was placed the new genus Panthera and so the name is now Panthera leo (Linnaeus, 1758) (Article 51.3).

This differs from botanical practice where the author of the current combination is appended to the name.

Last updated: 2010-04-29 11:58

How should names be punctuated?

Apart from brackets there must be no other punctuation between the species name and the name of the original author (Article 51.2). Punctuation can be used here however to indicate a citation instead (Article 51.2.1).

For example: Apis mellifera Linnaeus, 1758 means the bee species Apis mellifera was first published by Linnaeus in a paper or book published in 1758, whereas, Apis mellifera : Michener, 2000 means the bee species Apis mellifera was later referred to by Michener (2000).

See also the following chapters of the Code for full details of: the number of words in the scientific names of animals (Chapter 2); formation and treatment of names (Chapter 7); and authorship (Chapter 11).

Last updated: 2013-02-01 14:42

What are type specimens for?

What is a type?

Type specimens are the objective standard of reference for the application of zoological names. When a new species or subspecies is described, the specimen(s) on which the author based his description become the type(s) (Article 72.1). In this way names are linked to type specimens, which can be referred to later if there is doubt over the interpretation of that name. Consequently types are sometimes referred to as “onomatophores” which means name bearers.

Last updated: 2012-08-24 12:10

What kinds of types are there?

The following kinds of types are recognised by the Code. To avoid confusion no other terms should be used:

Syntypes – where a description has been based on a series of specimens, these collectively constitute the name-bearing type (Article 72.2-72.4; 73.2).

Lectotype – One of a number of syntypes which has been designated later as the single name-bearing type of a species, the remaining syntypes become paralectotypes and have no further name-bearing function (Article 74).

Paralectotype – see lectotype.

Holotype – A single specimen designated or otherwise fixed as the name bearing type of a species name when it was first described (Article 73).

Paratype – Where there is a holotype, the other specimens in the type series are paratypes (Rec. 73D), and they have no name-bearing function.

Hapantotype – A special kind of holotype in the case of extant protistans, which can consist of more than one individual (Article 73.3).

Neotype – A single specimen designated as the name-bearing type of a species name when the original type(s) is lost or destroyed and a new type is needed to define the species. Under exceptional circumstances the Commission may use its plenary powers to designate neotypes for example if an existing name bearing type is not in accord with prevailing usage (Article 75).

Allotype – a designated specimen of opposite sex to the holotype. This term has no name bearing function and is not regulated by the code (Rec. 72A).

Last updated: 2012-08-24 12:10

Do types have to be “typical” of a species?

No. The purpose of a type is purely nomenclatural, i.e. to determine the application of names. Types do not need to be typical in the sense of representing an average of the range of variation of a taxon, nor do they need to be a particular sex or life stage, or even a whole specimen.

Last updated: 2010-04-29 12:16

How can types be used to determine the application of names?

If the name-bearing types of two zoological names are considered to belong to the same taxon, then the two names are considered to be synonyms at the rank of that taxon. For example: the type specimens for the parasitic wasp names Trichopria aequata (Thomson, 1858) and Trichopria isis Nixon, 1980 are now considered to belong to the same species, consequently the names are synonymous and, according to the Principle of Priority (Article 23; glossary), assuming both names are not otherwise invalid, the older and valid name for this species is T. aequata. This is shown in the diagram below.

Last updated: 2013-02-28 10:26

What things can be types?

Only these things can be types (Article 72.5):

An animal.

Part of an animal.

The fossilised work of an animal (e.g. a burrow, track or footprint) or the work of an extant animal (e.g. a wasp nest) if named before 1931.

A natural colony of animals derived from a single individual e.g. a coral.

A naturally formed fossilised replacement, impression, mould, cast, in whole or in part, of an animal or colony of animals.

For extant protists, one or more preparations of a number of directly related individuals, which can include different life stages (a hapantotype).

A microscope slide containing one or more clearly marked individual animals.

Last updated: 2012-08-24 12:11

Can a photograph or holograph be a type specimen?

No, but the specimen depicted can be. Where a species name has been based on a photograph, illustration or description, the name-bearing type is considered to be the specimen(s) illustrated or described (Article 72.5.6; 73.1.4) the fact that the specimen is no longer extant does not mean that the species name is unavailable. While it is highly desirable to have a type specimen or part of a specimen permanently deposited in a museum or other publicly available collection, very occasionally it may be impractical, for example if it is unethical to kill or injure an individual of a highly endangered mammal. Other forms of evidence e.g. photographs, sonograms, may contribute to an original description in demonstrating that a type specimen existed, where the type specimen has to be released live. In these situations it is not necessary to deposit types in a Museum - the statement of intent to deposit types in a collection required for new species names published after 1999 is only necessary where types are extant (Article 16.4.2).

Last updated: 2012-08-24 12:11

Can DNA be a type specimen?

All animals originally contain DNA so except for preparations where the DNA has been destroyed or for fossils which don’t usually contain DNA, then DNA is often part of type specimens. Directly extracted DNA from an animal (i.e. not amplified) might theoretically be a type since as it is part of an animal (Article 72.5.1), however it is usually present in such small quantities that to study it further requires amplification, using a copying process such as the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) before sequencing. The copied DNA cannot be a type since it is not part of an animal nor does it fit any of the other categories of things that can be types. If the copied DNA is sequenced, a sequence can be regarded as a description of the DNA originally in the animal, so the type can be the specimen or part of the specimen, e.g. a tissue sample, or pre-amplification DNA sample, on which the sequence is based (Article 72.5.6). Consequently new species can be described on the basis of DNA sequences, and while not mandatory, it is strongly recommended that the type specimen(s) from which the DNA was sequenced is preserved and deposited in a museum with a type label and data linking it to the sequence (for example a GenBank number).

Last updated: 2012-08-24 12:11

The species I am studying has no type or an unidentifiable type: can I designate a neotype?

The problem of lost or destroyed or unrecognisable types is unfortunately a common one. A neotype designation is not always needed however because the identity of the species can often be recognised from:

- the original description;

- generally accepted interpretations that can be followed;

- examination of topotypic material, i.e. that collected at the type locality;

- or the problem can be set aside until more information becomes available which allows it to be resolved, e.g. if the original type is rediscovered.

The taxonomy of some animal groups which are soft bodied and hard to preserve can work reasonably well on this basis although many types are missing.

Sometimes however, the above approaches can be unsatisfactory and a neotype is needed. A neotype can be designated when no name bearing type (holotype, lectotype, syntype or previous neotype) for a species name is believed to be extant, i.e. it has been lost or destroyed, and where it is considered a name bearing type is needed to define the species (Article 75). Certain information must be published for the designation to be valid (Article 75.3):

- that there is an exceptional need;

- the taxon must be differentiated;

- details allowing recognition of the specimen;

- the reasons why it is thought the name bearing types are destroyed;

- evidence that the neotype is consistent with what is known of the former name bearing types;

- evidence that the neotype came from as close as practicable to the original type locality;

- and a statement that the neotype is or has become the property of an institution which can preserve it and make it available for study.

If the original name-bearing type is found then the neotype is set aside, unless this will cause instability, in which case the Commission can be asked to rule that the neotype is kept (Article 75.8).

Where an extant name-bearing type is unidentifiable, e.g. if very damaged, or a sex or life stage without diagnostic characters, then the Commission can be asked to set aside the extant name bearing type and a neotype can be designated (Article 75.5).

Last updated: 2012-08-24 12:11

What is the difference between availability and validity of names?

What is availability?

Availability is a kind of status which requires that a name must be taken into account as a part of zoological nomenclature. Names that are not available, effectively do not exist for the purposes of zoological nomenclature, and cannot enter into synonymy or homonymy, nor can they be used as the names of taxa.

Last updated: 2011-06-24 13:16

How does a name become available?

To become available, new names must be published following the criteria in Articles 1.3 & 10-20. The criteria have become stricter over time, reflecting improved standards in nomenclature. Some of the main criteria are as follows:

- Names must have been published after 1757 (Articles 8, 11.1)

- January 1st 1758 is taken to be the start of zoological nomenclature, and deemed to be the publication date of Linnaeus's 10th edition of Systema Naturae and Clerck's Aranei Svecici. These two works contain the first available names.

- Names must be spelled with the 26 letters of the Latin alphabet. Accents etc. do not make names unavailable but must be corrected (Article 11.2).

- The principle of binominal nomenclature must have been applied (Article 11.4).

- Genus and species names must contain two or more letters (Articles 11.8-9).

- Species names must be published with a genus name (Articles 11.9).

- Names published before 1931 can be accompanied by an indication instead of a description. E.g. an indication could be a reference to a previously published description, or even just an illustration (Article 12).

- Names published after 1930 must be accompanied by a description that is meant to distinguish the taxon from other taxa, or reference to previously published description or be new replacement names (Article 13).

- After 1930 genus names must have type species fixed (Article 13).

- After 1950 anonymously published names are not available (Article 14).

- After 1960 names published for varieties or forms are not available (Article 15).

- After 1999 new names must be indicated as new (Article 16).

- After 1999 type genera of family names must be cited (Article 16).

- After 1999 types must be explicitly fixed for species names (Article 16).

- Availability is not affected by the inappropriateness of names (Article 18).

E.g. the genus name for swifts Apus (from the Greek apous, meaning without feet) is still available, even though birds of this genus have feet.

Availability may be affected if there is more than one spelling (Article 19). - Names are not available for hypothetical concepts, teratological specimens, hybrid specimens, generally for names below the rank of subspecies (see also Article 10.2; 45.5-6), temporary names, and after 1930 for the work of animals (e.g. nests and tracks, see also Article 13) (Article 1.3).

E.g. the name Nessiteras rhombopteryx coined for the mythical Loch Ness Monster by Sir Peter Scott and Robert Rines in the journal Nature (vol. 258, pp. 466-468) is unavailable because it is a hypothetical concept. The name is also an anagram of Monster hoax by Sir Peter S. Journal editors beware! - A name that is not otherwise available can be ruled available by the Commission.

Loch Ness in Scotland, home of the mythical and hence unavailably named Nessiteras rhombopteryx, also known as the Loch Ness Monster.

Last updated: 2013-02-28 10:26

What is a nomen nudum?

A nomen nudum (plural nomina nuda) is a term used for a name which is unavailable because it does not have a description, reference or indication (specifically a name published before 1931 which fails to conform to Article 12, or after 1930 but fails to conform to Article 13).

Nomina nuda and other unavailable names can be made available if they are published again in a way that meets the criteria of availability; however, they are attributed to the author who first made them available, not the person who first used them.

Last updated: 2010-04-29 14:39

What is validity?

A valid name is the correct name for a taxon, i.e. the oldest potentially valid name of a name bearing type that falls with an author’s concept of the taxon (Chapter 6). “Potentially valid” means the name must be available, but not otherwise invalid for any other reason, such as being a junior homonym.

- The “principle of priority” is the principle that the valid name of a taxon is the oldest potentially valid name (Article 23). The purpose of this is to promote the stability of names.

- When two taxa are synonymised the valid name is determined by the principle of priority (Article 23.3).

- Similarly when two taxa are homonyms the valid name is determined by the principle of priority (Article 23.4, 52, Chapter 12).

- When two synonyms or homonyms are published at the same time the valid name is determined automatically if one is at higher rank (24.1) or by decision of the first reviser (24.2).

- The order of names within a work is not relevant – “page priority” is not generally recognized by the Code.

Sometimes what is valid can be a subjective judgment. E.g. if one taxonomist considers two names belong to one species, then he will treat the junior name as an invalid synonym, however if another taxonomist considers the names belong to different species, she will treat the junior name as valid. It is the task of the taxonomist and not the Commission to judge such subjective matters of taxonomic practice, however once decided the Code should allow the valid name(s) to be determined.

Last updated: 2010-04-29 14:44

Can a name be available but not valid?

Yes, e.g. a junior synonym or junior homonym can be available but not valid. Invalidity does not make a name unavailable (Article 10.6).

Last updated: 2010-04-29 14:52

How does usage affect availability and validity?

Available names which cannot be interpreted and are not used, e.g. if the type is missing, can be a problem for taxonomists. Such a name is often referred to as a nomen dubium (plural nomina dubia) or dubious name.

Such names do not become unavailable, even if they are not used as valid, they may become valid again in the future as they can continue to compete in homonymy and, if later applied to taxa, can compete in synonymy. This may be a problem for the stability of names e.g. as potential senior synonyms or homonyms may overturn the established usage of junior names.

The Code can allow prevailing usage to be kept where this will aid stability, even where this goes against the principle of priority. E.g. a forgotten name not used as valid since 1899, and found to be a senior synonym or homonym, can be declared a “nomen oblitum” and an established junior name for the same species a “nomen protectum”. This makes the junior name valid and the senior name invalid (Articles 23.2, 23.9.2). Difficult cases can be referred to the Commission for a ruling.

Last updated: 2010-04-29 14:53

I think I have a new species, how can I get it named?

How can I describe a new species?

The ICZN does not usually deal with the routine descriptions, naming and publishing of new species, this is a practical matter for taxonomists however the ICZN does define the rules which create the framework under which this can be undertaken.

Describing new species is a task for a specialist; much research may be needed to be sure a species has not already been described, and to decide if it is sufficiently different from existing species to describe. The characters considered diagnostic by taxonomists are often highly technical and specific to particular to groups of animals, so it is best to consult an expert in the group concerned. Taxonomic procedure is described in published works such as Winston, J. 1999. Describing species. Columbia University Press.

It is important for taxonomists to follow the rules set by the ICZN when describing species, these ensure, for example:

- the description is published in a work that is obtainable in numerous identical copies, as a permanent scientific record (criteria of publication, Chapter 3);

- the scientific name must be spelled using the 26 letters of the Latin alphabet; binominal nomenclature must be consistently used; and new names must be used as valid when proposed (criteria of availability, Chapter 4);

- that names are consistently formed following certain rules; that original spellings can be established (formation of names, Chapter 7);

- that names are based on name-bearing types, the objective standard of reference for the application of zoological names (Chapter 16);

- that general recommendations are followed for ethical behaviour (Appendix A);

- and that best practice should be used to give taxa names which are unique, unambiguous and universal (Appendix B).

Last updated: 2010-04-29 14:59

How do I name a species after someone?

Names based on personal names should follow Latin grammar; they may be a noun in the genitive case, a noun in apposition (nominative case) or an adjective or participle (Article 31). Of these a noun in the genitive case is recommended. This is formed by adding the stem of the name to a standard ending. A Latin equivalent for a personal name is often used. Names in languages using non-Latin characters can be transliterated into Latin characters. Some examples:

| Personal name | Latinised? | Stem of name | Gender ending | Species name |

| Margaret | No | margaret- | -ae (-ae for a woman) | margaretae |

| Margaret | Margarita or Margaretha | margarit- or margareth- | -ae (-ae for a woman) | margaritae or margarethae |

| Karl | No | karl- | -i (-i for a man) | karli |

| Karl | Carolus | carol- | -i (-i for a man) | caroli |

| Margaret and Jane Smith | No | smith- | -arum (-arum for more than one woman) | smitharum |

| Shawn and Jack Smith | No | smith- | -orum (-orum for a group of more than one man, or a mixed group) | smithorum |

| Margaret and John Smith | No | smith- | -orum (-orum for a group of more than one man, or a mixed group) | smithorum |

While there are different endings for male and female names, there is no implied value judgement in the endings.

Nouns in apposition are not recommended because the ending of the name is unchanged, and so it could be confused with an author name (Rec. 31A).

Adjectives based on the endings –anus/ -ana/ -anum or –ianus/ -iana/ -ianum are not recommended because they can sound rude, for example using the surname Bush could result in bushianus. Do not use a name which may cause offence (Appendix A); it is advisable to check with the person after whom the new species is being named that they are happy for their name to be used. Care should be taken because incorrectly formed names cannot always be changed afterwards (Articles 32, 34).

Last updated: 2010-04-29 15:01

Can I name a species after myself?

There is no rule against this, but it may be a sign of vanity!

Last updated: 2010-04-29 15:02

How can I check that a name I want to use has not been used before?

To avoid confusion it is important to avoid publishing a species name which is the same as one which has already been used for another species (a homonym). For example the crab names Cancer strigosus Linnaeus, 1761 and Cancer strigosus Herbst, 1799 are homonyms. Usually the younger name is invalid and has to be renamed to avoid confusion (Chapter 12).

The classic works of zoological nomenclature should be checked first, e.g. Index Animalium. For many groups of animals there are recent catalogues which can be checked to see which names have already been used. E.g. for mammals: Wilson and Reeder (2005) Mammal species of the World. Hopkins University Press. There are also web catalogues e.g. for fish - www.fishbase.org; for animals but with varying coverage - Integrated Taxonomic Information System www.itis.gov, and Animalbase www.animalbase.org;and for literature containing descriptions of new species - Zoological Record® database, http://thomsonreuters.com, available through specialist libraries. In some cases it is necessary to undertake a library search to trace species names in the original literature.

Last updated: 2010-04-29 15:05

If I find a name is incorrectly spelled, what do I do?

What is the importance of spelling?

For names to be stable it is important to determine the correct original spelling, recognise incorrect spellings and correct them if needed (Article 32). The rules are aimed at forming names in accordance with the principles of binominal nomenclature (Article 5) but avoiding unnecessary changes which would cause instability.

Last updated: 2010-04-29 15:12

What is the correct original spelling?

The term “correct original spelling” has a special meaning which is different from what is commonly understood by correct spelling. Names are assumed to be spelled correctly in the work where they were established except if they are incorrect because of one of the reasons given in article 32.5, e.g.:

- if there is evidence in the work of a spelling or printer’s error, e.g. a species was said to have been named after Linnaeus, but the name is spelled ninnaei, when it should have been linnaei, it is to be corrected;

- if the name is published with an accent, apostrophe, numbers, spaces, abbreviations, or other symbol than the 26 letter Latin alphabet, then these are to be corrected;

- hyphens are similar but are retained where the first letter is describes a character of the species for example in the butterfly name Polygonia c-album refers to a white c-shaped mark on the wing.

However incorrect Latinization is not to be corrected (Article 32.5.1).

Incorrect endings may also need to be corrected (Article 34) e.g.:

If the ending of a species name which is an adjective does not agree with the gender of the genus then it has to be corrected.

However names based on personal names with incorrectly Latinized endings are not corrected as this would cause instability (Article 32.5.1, glossary definition of Latinization). I.e. a species which was named smithi after a woman with the surname smith is not incorrectly spelled even though the normal feminine Latinization is smithae.

Last updated: 2011-08-09 16:47

What if the spelling is changed later?

Where a subsequent spelling differs from the original, it can be either:

- a “mandatory change” if needed to correct the ending (Art. 34) such as when a species name is combined with a different genus, it may need to change ending to agree with the gender of the genus. This is effectively the same name and retains the same author and date.

- an “emendation” if a demonstrably intentional change (Art. 33.2) not required by Article 34. An emendation may be:

- a “justified emendation” (Art. 33.2.2) if corrected under article 32.5. This retains the same author and date as the original name.

- or an “unjustified emendation” (Art. 33.2.3) if not corrected under article 32.5. An unjustified emendation is available with its own author and date and is usually a junior synonym of the name in its original spelling. Rarely an unjustified emendation can become a justified emendation if in prevailing usage (Art. 33.2.3.1)

- or if neither a mandatory change or emendation, it is an “incorrect subsequent spelling” (Art. 33.3). An incorrect subsequent spelling is not an available name. Rarely it can become the correct original spelling if in prevailing usage (Art. 33.3.1).

More detail on the spellings of names can be found in Articles 11 and 25-34; species group names in Articles 11.9 and 31; genus group names in Article 11.8; and family group names in Article 11.7 and 29.

Last updated: 2010-07-21 11:28

What are the critical works in zoological nomenclature?

What are the critical works in zoological nomenclature

- The 10th edition of the Systema Naturae, published in 1758 by Linnaeus, is the official starting point for zoological nomenclature. In this work Linnaeus adopted binominal names for species of animals.

- Index Animalium by Charles Davies Sherborn, is a complete list of all the generic and specific names that have been applied by authors to animals since January the first, 1758 with exact date and reference, until 1922.

- Nomenclator Zoologicus, by Sheffield Airey Neave, the bibliographical origins of the names of every genus and subgenus in zoology published from 1758 – 2004.

- Zoological Record, world's oldest continuing database of animal biology with coverage back to 1864.

- ZooBank - The Official Online Registry for Animal Nomenclature (in development).

- “The Code” The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature.

- The Official Lists and Indexes of Names and Works in Zoology, details of all the names and works on which the ICZN has ruled.

- A review of classics in zoological nomenclature is available in: Polaszek, A. & E. Michel, 2010. Linnaeus – Sherborn – ZooBank. In: Systema Naturae 250 The Linnean Ark. A. Polaszek, Ed. CRC Press. P. 163-172. See other papers in the same volume.

- A recent symposium on nomenclature with contributed papers: Updating the Linnaean Heritage: Names as Tools for Thinking about Animals and Plants, A. Minelli, L. Bonato & G. Fusco, Eds. Zootaxa 1950: 1-163 (5 Dec. 2008), ISBN 978-1-86977-297-0.

Last updated: 2010-07-21 11:35

Selling scientific names

What is the ICZN official position on selling scientific names?

There is no official position taken by the Commission.

Last updated: 2010-07-21 11:47

What are the pros (advantages) of selling scientific names?

Funding for research in taxonomy and for conservation is difficult to obtain, and selling the rights to name an organism can provide a direct source of support for these activities. Putting an explicit price on the discovery and description of new species provides value in terms that people can relate to personally and immediately, a monetary value. This is often easier for people to connect with than the other values associated with biodiversity which tend to be moral, philosophical, religious, aesthetic, scientific or ecologically functional. It also gives recognition to the work of species discovery, in the way a financial prize draws attention to an honour conferred on an artist – it is not the money per se, it is the recognition that goes with it. Selling names can engage the public in biodiversity by providing a potential for perceived ‘ownership’. Sponsorship and patronage has always been a part of scientific exploration, and it is argued that this is no different.

Last updated: 2010-07-21 11:48

What are the cons (disadvantages) of selling scientific names?

There is concern that selling the products of taxonomic work as individual units can distort the scientific process. Would it lead to increased splitting of taxa? For example, if a taxonomist is uncertain about whether to split or lump a taxon, the financial incentive might swing the balance so that double the profit could be made from the same work! Other questions come to mind. What happens if a name is sold but the paper publishing it is never written (thus it is not available under the Code)? What if the name is synonymized after the deal is done? Would the country of origin of the taxon be able to claim ownership of the proceeds from the sale of naming rights? Would a biodiversity-rich country be justified in raising its rates for research permits in anticipation that profit might be made from this aspect of the results of taxonomic exploration? Will much larger grants and even more complicated memoranda of understanding, be needed to cover the financial interests that have crept in to taxonomy through this means? Will institutions auction off the work of their scientists to help fund taxonomic research, but thereby remove one of the rewards of what is often perceived as otherwise punishing work, the privilege of choosing a name? Could there even be a total loss for the taxonomist, whereby they lose the right to choose a name due to its sale, and then the funds get claimed by the home country for the organism as a share of commercial profit from bioexploration?

In addition, while the charitable aspects are laudable and in some cases very successful, in other cases of selling names it is not clear how much of the price paid actually returns to those who need it most. There are also concerns that while naming charismatic species can command high prices, the taxa, ecosystems and taxonomists who need the support the most will not be able to raise funds this way. This could lead to a dreary situation that they become doubly disadvantaged, if the administrations that oversee them might expect them to raise research funds through selling names, but there are no buyers for their non-celebrity uncharismatic taxa.

A further set of objections revolve around the recommendations that scientific names should have some connection with the organism such as a descriptive aspect, its place of origin, an honourific for someone in the field (not a purchaser after the fact). People buying names may not want to give a biologically or geographically predictable name to the taxon.

Monetizing biodiversity is indeed a challenge.

Links to articles and examples

- http://supportscripps.ucsd.edu/Areas_to_Support/Support_Collections/Name...

- http://www.biopat.de/englisch/index_e.htm

- http://www.biopat.de/englisch/wiss_info/ko_richtl.htm

- http://www.nameaspecies.com/

- http://wildfilms.blogspot.com/2008/07/scientific-names-for-sale.html

- http://legacy.signonsandiego.com/news/metro/20080406-9999-1n6naming.html

- http://explorations.ucsd.edu/Around_the_Pier/2008/July_August/Name_a_Spe...

- http://www.washingtonpost.com/wpdyn/content/article/2007/09/21/AR2007092...

- http://www.washingtonpost.com/wpdyn/content/article/2007/09/13/AR2007091...

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Madidi_Titi

- http://www.goldenpalacemonkey.com/

- the harder perspective taken by astronomers: http://iau.org/public/buying_star_names/

Last updated: 2010-08-17 17:02

ZooBank and registration of nomenclatural acts

I've just described/reassigned a species. Do I need to register my publication in ZooBank?

Yes, nomenclatural acts published in electronic publications need registration in ZooBank to be available.

The 2012 Amendment to the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature allows electronic publication for nomenclatural purposes if certain requirements are fulfilled. We here explain these simple requirements, including what needs to be registered in ZooBank and when, which version of an electronic work is potentially Code-compliant (only the final, immutable version), and what is the correct date of publication (that of the final, immutable version; pre-final versions posted online are preliminary and as such always unavailable). We advise registration in ZooBank of publications that are issued in both electronic and paper version to secure the nomenclatural priority of the generally earlier electronic version. Failure to update a ZooBank record after publication will not have any impact on availability under the Code but will keep the registered information hidden from public view. Publishers may want to consider automated registration as an integral part of the publishing process; this has already been shown to be feasible and would ease the burden of manual registration for editors and authors.

Last updated: 2015-11-11 02:55

What is the status of the ICZN ruling on electronic-only publication of nomenclatural acts?

Following four years of highly charged debate, the rules for publication of scientific names of animals have been changed to allow electronic publications to meet the requirements of the stringent International Code of Zoological Nomenclature. In a landmark decision, the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) has passed an amendment to its rules that means a publication in an electronic-only scientific journal will be ‘legitimate’ if it meets criteria of archiving and the publication is registered on the ICZN’s official online registry, ZooBank.

For more information see the articles published today in the journals ZooKeys and Zootaxa, and the press releases below.

ICZN Amendment_E-publication-PressReleaseV4-short (DOC)

ICZN Amendment_E-publication-PressReleaseV2-long (DOC)

Amendment to Code (PDF)

Last updated: 2012-09-04 08:00

How can I help the ICZN?

How can I make a donation and what will it be used for?

The ICZN activities depend to a crucial extent on donations from individuals, institutions, learned societies and grant-giving bodies to enable the Commission to continue its important work.

Our fundraising addresses two sets of needs – operational and project costs. Your donations will help defray operational costs such as the running of the Secretariat, publication of the journal Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature, and travel expenses for the Commissioners (who otherwise perform their duties unpaid) and through the latter you can fund projects such as ZooBank or development of the 5th Code.

Please click here for more information on how to donate to the ICZN.

Last updated: 2019-02-22 16:19

How can I help improve the practice of good scientific nomenclature?

Participate in discussions of issues in nomenclature online, especially on Taxacom and the ICZN listserver.

Are you a biologist? It is also a benefit to the taxonomic community and the future stability of scientific names of organisms if you can include a section on nomenclature in your teaching. We are building up a set of teaching tools which you are welcome to use, and welcome to provide further contributions.

Are you an editor for a biological journal? Ensure the rules of nomenclature are followed by your contributing authors. If you have questions, contact the ICZN Secretariat (iczn (at) nus (dot) edu (dot) sg) or post a question on the taxonomy and nomenclature listservers.

Last updated: 2019-02-22 16:22

Who is the type of Homo sapiens?

Who is the type of Homo sapiens?

by David Notton and Chris Stringer

In Linnaeus' 10th edition of Systema Naturae (Linnaeus, 1758) he named four geographical subspecies of Homo sapiens: europaeus, afer, asiaticus and americanus, introducing some anecdotal behavioural distinctions in line with then current European notions about their own superiority. For example while europaeus was, of course, 'governed by laws', americanus was governed 'by customs', asiaticus 'by opinions', and the African subspecies afer 'by impulse'. While not wishing to revisit such dubious notions here, one continuing issue over Linnaeus' naming of Homo sapiens remains a topic of discussion: the designation of a type specimen. What follows is our view of the nomenclatural issues, and the appropriate designation.

The type specimen of Homo sapiens is Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778). In Linnaeus' 10th edition of Systema Naturae (Linnaeus, 1758) which is taken to be the starting point of zoological nomenclature, he described Homo sapiens including 6 named subgroups, i.e. ferus, americanus, europaeus, asiaticus, afer and monstrosus. Ferus and monstrosus are infrasubspecific because the content of the description shows that ferus is used for feral children, those found in the wild, differing only as a consequence of their upbringing, and monstrosus is used for a mix of unrelated forms (part a) and people with modifications of the body due to human artifice (part b). Consequently ferus and monstrosus are not available names and do not enter into zoological nomenclature. This leaves as available names americanus, europaeus, asiaticus, and afer, which are subspecific names of Homo sapiens (Article 45.6). Also from the principle of coordination there must be a subspecific name sapiens, and the type of Homo sapiens is by definition the type of the subspecies Homo sapiens sapiens (Article 43).

Linnaeus did not designate a type for Homo sapiens or any of its nominal subspecies - that was not the custom then. However, the type series consists of all the specimens he included (Article 72.4) according to the characters given in his descriptions. The description of Homo sapiens is drawn broadly; it spreads over five pages, starting ³1. H[omo] diurnus; varians cultura, loco. ² Then describing the 6 subgroups, continuing with the general description from the end of the description of monstrosus to page 24, from ³ Habitat inter TropicosŠ² to ³Pedes Talis incedentes². The description for Homo sapiens sapiens is all the parts of the description that do not include the named subgroups and similarly the type material is all those specimens included by Linnaeus, not including those referred to under the named subgroups (Article 72.4.1).

It is certain that Linnaeus was present when he wrote this description and that he regarded himself as included in Homo sapiens. That he is not part of any of his subgroups is clear from the descriptions, in particular he is certainly not part of Homo sapiens europaeus since this subspecies is described as 'Pilis flavescentibus, prolixis. Oculis caeruleis' whereas Linnaeus has brown hair and eyes (Tullberg, 1907). He is therefore included in the type series of Homo sapiens sapiens (Article 72.4.1.1). There was, however, no single person recognised as the type until 1959, when Professor William Stearn, in a passing remark in a paper on Linnaeus's contributions to nomenclature and systematics wrote that 'Linnaeus himself, must stand as the type of his Homo sapiens'. This was enough to designate Linnaeus as a lectotype (Article 74.5), the single name bearing type specimen for the species Homo sapiens and its subspecies Homo sapiens sapiens.

Carl Linnaeus (Carl von Linné), 23 May 1707 Â 10 January 1778: The lectotype of Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758 designated by Professor William Stearn in 1959 (Swedish National Museum, Stockholm).

Carl Linnaeus (Carl von Linné), 23 May 1707 Â 10 January 1778: The lectotype of Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758 designated by Professor William Stearn in 1959 (Swedish National Museum, Stockholm).

From a practical point of view the designation of Linnaeus as lectotype is of limited value, since there is no doubt over the identity of the species Homo sapiens. For the same reasons there is no exceptional need for the designation of a neotype. His remains are not lost (the tomb is in Uppsala Cathedral in Sweden), but it would be unethical to disturb them and anyway there is no need for them to be re-examined in order to establish the application of this name. However, it is symbolic that Linnaeus as the father of modern taxonomy should have been designated.

It is important to be clear about the type status of Linnaeus because there have been misapprehensions about who the type is, which cause confusion. For example, the story that Edward Cope is the type. This error deserves little attention except that it has been given credence on the internet and by some popular science journalists, so it is worth briefly explaining why it is wrong. In a book about dinosaurs published in 1994, Louie Psihoyos reported a proposal by Bob Bakker to designate Cope as a lectotype for Homo sapiens. The proposal was never actually published by Bakker, but was reported by Psihoyos in sufficient detail to serve as a designation in its own right. Psihoyos' designation was invalid because:

- Cope was not eligible for selection as a lectotype because he wasn't among the specimens/people included by Linnaeus when he made his description (Article 74.1) - Homo sapiens was described in 1758 but Cope wasn't born until 1840, almost 100 years later, so he definitely wasn't included by Linnaeus.

- Stearn's valid designation in 1959 already existed before Psihoyos's designation in 1994 and no designations after Stearn's can be valid (Article 74.1.1).

So it's absolutely clear Cope never could be a lectotype. For a more detailed explanation see the excellent paper by Spamer (1999).

Last updated: 2013-02-28 10:26

Is there such a thing as "page priority"?

Is there such a thing as page priority?

By Thomas Pape

Generally no. The page, or position on a page, on which a name (or act) appears does not in itself influence its precedence relative to other names (or acts) in the same work.

The valid name of a taxon is the oldest available name applied to it, unless this name is invalidated by one of the provisions of the Code or by a ruling by the Commission. Thus, the precedence, i.e., the order of seniority of available names or nomenclatural acts, is determined by the dates on which the works containing the names or acts were published. If two names that are found to be synonyms were published in the same work, they are simultaneously published and equally old (unless the work was issued in parts at different dates and with the names in different parts).

The order of precedence of simultaneously published names or acts is determined by the first reviser or by a ruling of the Commission using its plenary power. The first reviser is that author who first selects one of two (or more) simultaneously published names considered synonymous (or different original spellings of the same name) to have precedence over the other name(s).

The one exception (recommendation 69A.10) is that when designating the type species for a genus, all other things being equal (i.e. a choice cannot be made on the basis of recommendations 69A.1-9), an author should give preference to the species cited first in the work, page or line. This is known as “position precedence”.

Last updated: 2010-09-29 15:44

Phylocode

Should I use Phylocode?

There is nothing to force anyone to use or not use the Phylocode (PC), or the established ICZN code (the Code). However, and it is a big however, the ICZN Code is effectively universally used by zoologists and required by editors (where they are well enough informed to know what the rules are) because it has been the standard for a long time (essentially 100+ years for the Code in its various versions and 250 years for Linnaean binominal names on which it is based) and is the product of international agreement among scientists (who worked together despite world wars, etc). PC is not adhered to by a majority of working taxonomists, is strongly criticised by many, e.g. Phylocode debate; Wheeler. 2004. Taxonomic triage and the poverty of phylogeny. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 2004 359, 571-583.; Knapp et al. 2004. Stability or stasis in the names of organisms: the evolving codes of nomenclature. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B (2004) 359, 611–622.

The ICZN Code should be used in preference to Phylocode because the ICZN Code supports nomenclature which is specific, stable and effective enough to provide a consistent means of communication between scientist, and flexible enough to accommodate new information. It is usefully independent of philosophy and politics as to be universally and internationally applicable but at the same time is compatible with phylogenetic and most other conceivable theories of classification. It has the broad mandate of the scientific community and accommodates and gives context to the rich inheritance of the past 250 years of Linnean nomenclature.

Last updated: 2019-02-22 16:41

What are the main differences between the ICZN Code and Phylocode?

There are three main differences:

- philosophical;

- mandate;

- general practicalities of adoption.

Last updated: 2010-09-29 15:48

Why is the philosophy of Phylocode not universal?

The main difference between the ICZN Code and Phylocode is philosophical. PC assumes adherence to a particular philosophy of phylogenetic definitions which underpin the way it requires scientists to define and hence name clades, whereas, the ICZN Code is independent as far as possible of scientific (and especially taxonomic) judgments. This is very clear from the Introduction which says “The … Code…, has one fundamental aim, which is to provide the maximum universality and continuity in the scientific names of animals compatible with the freedom of scientists to classify animals according to taxonomic judgements” and principles 1-4 go on to say that the Code should refrain from “infringing on taxonomic judgement” or “taxonomic freedom”. The reason why this is so important is because it allows the Code to be universal, i.e. used by all scientists as the standard way of communicating scientific names. PC cannot be used this way because those who did not share the phylogenetic philosophy would not be able to use it, at least without compromising their scientific independence. The past 100 years have shown that the Code has been able to accommodate the numerous schools of taxonomic philosophy that have come and gone, and there is no reason why it cannot satisfactorily accommodate phylogenetics. Indeed most phylogenetic taxonomists (the vast majority of taxonomists today) do use the Code. No doubt the philosophy of PC will come and go the way other such philosophies have done in the past. In connection with this, another difference is that the ICZN takes commissioners from any taxonomic philosophy and with no membership criteria, whereas the Committee on Phylogenetic Nomenclature (CPN) members are elected only from the International Society of Phylogenetic Nomenclature, which although it says it has no membership restrictions, its stated purpose is to promote a specific phylogenetic nomenclature, an aim which would exclude many from wishing to be members.

Last updated: 2010-09-29 15:49

What mandate does Phylocode have?

A second major difference between Phylocode and the ICZN Code is that PC does not have the same mandate from the scientific community. The Code is ratified by the Executive Committee of the International Union of Biological Sciences acting on behalf of the Unions General Assembly, part of the International Council of Science. The ICS is a non-governmental, non-profit body representing an international membership of numerous affiliated scientific bodies, and consequently the wider scientific community of biologists, the end users of taxonomy who we should be serving. Phylocode has no such mandate.

Last updated: 2010-09-29 15:50

What are the practical difficulties in using Phylocode?

There are many practical problems with the proposal to adopt PC, for example:

- Adoption would cause major instability both in the change over period which would require two codes working in parallel and according to some it would also be more unstable when adopted. The ICZN has worked very hard for the existing state of stability, and this would be a significant step backwards.

- PC does not cover species names, so the Code will still be needed for these, there is no philosophical reason for this inconsistency, merely the PC cannot practically “convert” the existing animal species names to phylogenetic definitions in the foreseeable future with the resources they have.

- Even if PC is adopted for names above the species group, not everyone will adopt PC, so there would be the problem of coexistence with names diverging in meaning, undergoing different nomenclatural treatment by each code, and the resulting confusion.

- PC is only a draft at present, so it is not in force, currently there is no clear indication when or if it will become active; it may turn out to be a “castle in the air”.

- • PC is in effect untested in the real world, whereas the Code has 100+ years of development and combined experience of what works and what doesn’t (see the extensive ICZN publications of Cases official Opinions etc.). This is not to say that the Code is perfect, it is currently evolving to be fit for the 21st century. For example there are initiatives to implement centralised registration of names and develop an authoritative list of available names in an electronic tool called “Zoobank”; to change the rules on what constitutes valid publication to accommodate electronic publication modes; and to restructure the Code in its next (5th) edition. These are challenging topics, however the ICZN is likely to carry these forward with more success than PC because ICZN is already well advanced in these topics and has a more universal mandate.

Last updated: 2010-09-29 15:52